[ad_1]

Power Innovation companions with the unbiased nonprofit Aspen International Change Institute (AGCI) to supply local weather and power analysis updates. The analysis synopsis beneath comes from AGCI Program Director Emily Jack-Scott and a full listing of AGCI’s quarterly analysis updates protecting latest local weather change analysis on clear power pathways is accessible on-line at https://www.agci.org/options/quarterly-research-reviews

Representatives and scientists from almost 200 nations are within the technique of rigorously vetting a abstract for policymakers of the Intergovernmental Panel on Local weather Change (IPCC)’s Sixth Evaluation Report of how the local weather has already modified and what we are able to anticipate in coming a long time. The three-part evaluation would be the most significant and complete reference but for informing worldwide negotiations to curb catastrophic human-caused local weather change. Crafting the policymaker abstract comes within the lead-up to this November’s COP26 UN Local weather Change Convention, in addition to the beginning of the two-year International Stocktake course of. In contrast to previous reviews, this one will element regional local weather change and impacts in addition to “tipping factors,” which might set off pure processes to rework into dramatically completely different and sure irreversible states (for instance, the melting of the Greenland ice sheet).

Forest and Fields, Rondônia, Brazil, July 18, 2016; Farms and pastureland carve their means into tropical forestland within the western Brazilian state of Rondônia. The state is likely one of the Amazon’s most deforested areas. Supply: Planet Labs, Inc., CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, by way of Wikimedia Commons.

One such important tipping level is the potential transformation of the world’s largest tropical forests from carbon sinks into web sources of carbon emissions. At the moment, carbon emissions that end result from deforestation and forest degradation (also known as land-use change) are offset, partly, by new reforestation and regrowth. The remainder of these emissions are absorbed by intact forests together with further emissions from fossil gasoline combustion, making forests a web carbon sink. Intact tropical forests, specifically, play an outsized function in carbon uptake, to say nothing of their wealth of biodiversity (a single hectare of tropical forest can include as many plant species as all of the native species of western Europe). However how lengthy can tropical forests stay one in every of Earth’s biggest carbon sinks? How is local weather change affecting this capability?

This tipping level for tropical forests has been difficult for researchers to foretell. One purpose is that disproportionately few floor observations have been made in tropical forests in comparison with mid-latitude forests (particularly these within the Northern Hemisphere). Whereas latest advances in satellite tv for pc knowledge and distant sensing have helped compensate for the dearth of floor observations, we lack actual estimates of how a lot carbon is being emitted and absorbed—known as carbon fluxes—by tropical forests. The uncertainty usually stems from variations in frameworks, definitions, and resolutions utilized in analyses. The approaches usually yield comparable outcomes, however even small variability in findings has made it difficult to establish which forests are carbon sinks, impartial, or sources.

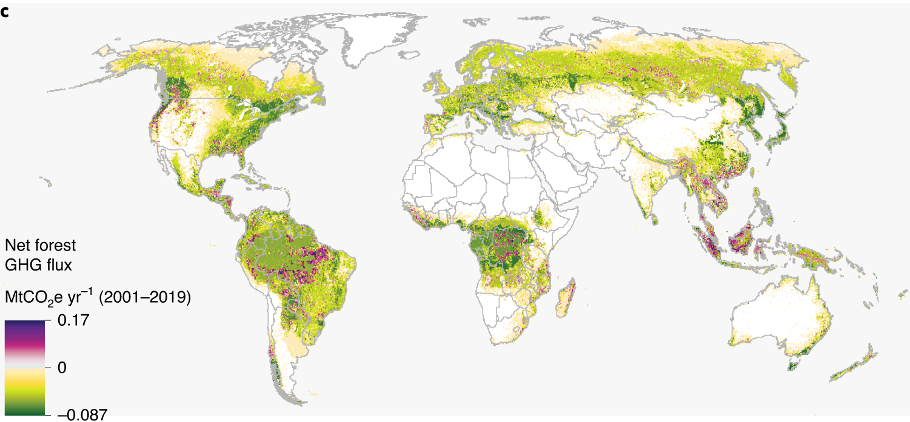

For a while, researchers questioned if local weather change would enhance tropical forests’ long-term skill to soak up carbon. Larger focus of atmospheric carbon dioxide can enhance tree development (CO2 fertilization); conversely, extra frequent droughts are identified to lower annual tree development and escalate tree mortality. Local weather change is driving each phenomena. And these have to be weighted alongside different key variables like charges of pure forest regeneration (as a carbon sink) and in depth forest degradation, fires, fragmentation, and clearing (as carbon sources). This creates the situations for a carbon flux tug of battle between carbon removals (positive aspects) and emissions (losses) (Determine 1).

Determine 1. Web annual GHG flux. For show functions, maps have been resampled from the 30-m statement scale to a 0.04° geographic grid. Values within the legend mirror the typical annual GHG flux from all forest dynamics occurring inside a grid cell, together with emissions from all noticed disturbances and removals from each forest regrowth after disturbance and removals occurring in undisturbed forests. Supply: Harris et al., 2021.

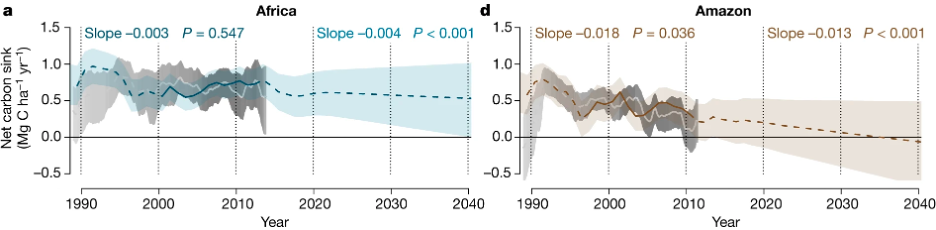

Hubau and colleagues launched a groundbreaking research in Nature in 2020 analyzing in depth floor observations from 1985 to 2014 throughout Amazonian and African tropical forests. Investigating environmental drivers of noticed carbon fluxes alongside further explanatory variables utilizing a carbon-gain mannequin, they had been capable of attribute competing optimistic and detrimental drivers of carbon positive aspects.

In each areas, they attribute a 3.7 % enhance in positive aspects to CO2 fertilization—however from there, the outcomes start to diverge. Features in African tropical forests had been marginally tempered by carbon losses attributable to droughts (-0.5 %) and elevated temperature (-0.1 %). In Amazonia, these losses had been considerably extra pronounced, with droughts accounting for two.7 % of carbon losses and elevated temperatures inflicting a further 1.1 % loss. Latest droughts in 2005 and 2010 resulted in markedly increased carbon losses by spikes attributable to tree mortality.

Determine 2: Modeled previous and future carbon dynamics of structurally intact old-growth tropical forests in Africa and Amazonia. Predictions of web aboveground dwell biomass carbon (a, d), for African (left) and Amazonian (proper) plot stock networks, based mostly on CO2-change, MAT, MAT-change, drought (MCWD), plot wooden density, and plot CRT, utilizing observations in Africa till 31 December 2014 and Amazonia till mid-2011, and extrapolations of prior developments to 31 December 2039. Mannequin predictions are in blue (Africa) and brown (Amazon), with stable strains spanning the window when ≥75 % of plots had been monitored to point out mannequin consistency with the noticed developments, and shading displaying higher and decrease confidence intervals accounting for uncertainties within the mannequin (each fastened and random results) and uncertainties within the predictor variables. Gentle-gray strains and grey shading are the imply and 95 % confidence interval of the observations from the African and Amazonian plot networks. Supply: Hubau et al., 2020.

However why within the Amazon and never in Africa? Hubau and colleagues level to differing situations—for example, African tropical forests are on common 1.1°C cooler and develop at increased elevations than their Amazonian counterparts. In addition they level to findings from their carbon gain-and-loss mannequin displaying that Amazonian timber retain beforehand absorbed carbon for shorter intervals (common of 56 years) than African timber (common of 69 years). We will due to this fact anticipate to see better carbon losses from African forests about 10-15 years after the Amazon, with a projected 14 % decline in aboveground biomass carbon sink by 2030 (as in comparison with the 2010-2015 imply) (Determine 2a). Much more sobering, the researchers undertaking the Amazon sink will proceed to say no all the way in which to zero by 2035 and thereafter function a web supply of carbon (Determine second).

Gatti and colleagues revealed a 2021 analysis article reinforcing that the Amazon forest is dwindling in its function as a carbon sink. The japanese (and significantly southeastern) areas of the Amazon have seen a marked enhance in deforestation, warming, drought, and fires during the last 40 years. These drivers are self-perpetuating—creating even drier situations and additional exacerbating tree mortality, diminished photosynthesis, and better carbon emissions. Saatchi and colleagues equally name consideration to the diminishing sequestration capability of the Amazon and underscore the function of land-use stressors like deforestation within the transition, with local weather change as a secondary driver. They, like Hubau, additionally level to attainable forest dynamics at play, whereby the Amazon’s tree species are much less drought tolerant than Africa’s, hampering resilience to land-use and local weather stressors working in live performance.

Hubau’s findings despatched a robust sign that the world’s largest tropical forests have already reached or are nearing their “saturation factors,” at which they’ll not soak up extra carbon than they produce. In truth, the research suggests tropical forests’ peak sequestration capability occurred within the Nineteen Nineties, and has decreased by about 50 % from the Nineteen Nineties to 2000s. Between 1990 and 1999, intact tropical forests had been answerable for about 50 % of all of Earth’s terrestrial sink (17 % of complete international anthropogenic CO2 emissions). However within the final decade, that has dropped to solely 20 % (or 6 % of complete emissions).

A publication by Koch and colleagues builds upon Hubau’s analysis, displaying that the saturation and decline in carbon uptake has not been captured by Earth System Fashions (each CMIP5 and CMIP6). Even in essentially the most pessimistic of situations, tropical forests are represented in mannequin carbon dynamics as a modest web carbon sink for the subsequent a number of a long time.

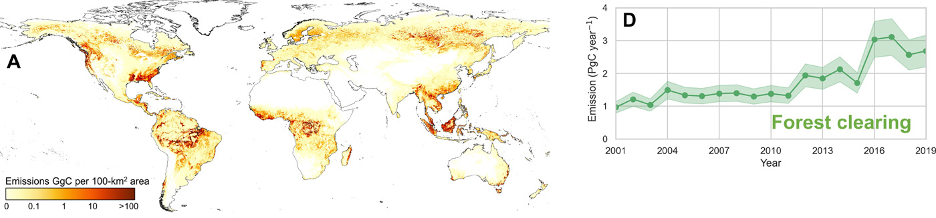

So what could be finished? Authors similar to Harris and Xu reinforce the significance of curbing deforestation, which has risen precipitously within the final decade (Determine 3 a, d). That is particularly essential in carbon-rich tropical forests within the Amazon, Africa, and Southeast Asia, that are liable to bigger carbon fluxes. Xu additionally notes the impression of prioritizing secondary forest restoration in tropical ecosystems.

Determine 3. Emissions from forest clearing from 2000 to 2019: (A) spatial distribution of common emissions from forest clearing [gigagrams carbon (GgC) year–1] from forest degradation estimated for pantropical areas, and time collection of annual emissions and uncertainty from (D) forest clearing. Supply: Xu et al., 2021.

Governments are inspired to make use of new frameworks to trace and analyze knowledge related to their forest-based mitigation targets. Harris underscores the chance to implement an internationally constant forest monitoring community, which may additionally profit non-governmental organizations and firms seeking to cut back their supply-chain emissions. Xu and colleagues reinforce this advice for the International Stocktake, urging decision-makers to benefit from stock frameworks that may present knowledge on subnational and regional scales.

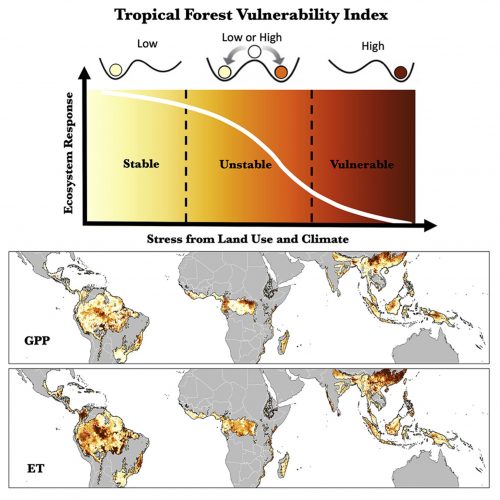

Determine 4. Maps of vulnerability of humid tropical gross major productiveness (GPP) and evapotranspiration (ET). Supply: Saatchi et al., 2021.

Determination-makers taking part in COP26 and the International Stocktake may now use a newly launched tropical forest vulnerability index produced by Saatchi and colleagues. This primary-of-its-kind index can spotlight particularly susceptible subregions throughout the world’s tropical forests, based mostly on quite a lot of ecologically essential response variables (Determine 4). It may be used to sign early warnings for areas in peril of transitioning into new and irreversible states. The vulnerability index will regularly enhance with longer satellite tv for pc knowledge information and anticipated advances in satellite tv for pc observations. Notably, it doesn’t but seize socioecological vulnerabilities from declining ecosystem capabilities and livelihoods.

As decision-makers contemplate choices for pure local weather options by sequestration in tropical forests, Koch and colleagues advocate contemplating the impression of choices throughout the Earth system as a complete. The staff carried out an idealized experiment in a totally coupled emissions-driven Earth system mannequin wherein all land-use conversion was ceased in international tropical forests, permitting for restoration. Whereas they noticed considerably elevated carbon sequestration in tropical aboveground biomass (and myriad biodiversity advantages), that sequestration didn’t translate right into a notable discount of worldwide floor air temperatures by 2100 in comparison with the management state of affairs. The authors attribute this to the truth that in a management state of affairs, there’s better sequestration by oceans and biomass in temperate and boreal areas.

They emphasize that these findings don’t negate the significance of halting deforestation in tropical forests. Reasonably, they encourage decision-makers to acknowledge that sequestration doesn’t function a substitute for lowering fossil gasoline emissions. Widespread restoration additionally performs a useful function in lowering peak atmospheric CO2 and temperatures within the subsequent few a long time, throughout which era further detrimental emissions applied sciences could be scaled up. It additionally reduces the carbon uptake required by the ocean (and related impacts on marine methods). Moreover, halting deforestation and degradation of tropical forests will probably be important for species migration and survival over the approaching centuries.

A number of researchers drive house the significance of co-developing options inside native contexts and with stakeholder enter. With out query, preserving and restoring the world’s most carbon-rich, biodiverse forests is a high precedence for curbing the worst impacts of local weather change. With unprecedented entry to knowledge by increasing on-the-ground analysis networks and superior satellite tv for pc knowledge, decision-makers are higher outfitted than ever to know the function tropical forests can play in pure local weather options and related tipping factors.

Featured analysis

Gatti, L.V., Basso, L.S., Miller, J.B., Gloor, M., Domingues, L.G., Cassol, H.L., Tejada, G., Aragão, L.E., Nobre, C., Peters, W. and Marani, L., 2021. Amazonia as a carbon supply linked to deforestation and local weather change. Nature, 595(7867), pp.388-393.

Harris, N.L., Gibbs, D.A., Baccini, A., Birdsey, R.A., De Bruin, S., Farina, M., Fatoyinbo, L., Hansen, M.C., Herold, M., Houghton, R.A. and Potapov, P.V., 2021. International maps of twenty-first century forest carbon fluxes. Nature Local weather Change, 11(3), pp.234-240.

Hubau, W., Lewis, S.L., Phillips, O.L., Affum-Baffoe, Ok., Beeckman, H., Cuní-Sanchez, A., Daniels, A.Ok., Ewango, C.E., Fauset, S., Mukinzi, J.M. and Sheil, D., 2020. Asynchronous carbon sink saturation in African and Amazonian tropical forests. Nature, 579(7797), pp.80-87.

Koch, A., Hubau, W. and Lewis, S.L., 2021. Earth System Fashions usually are not capturing current‐day tropical forest carbon dynamics. Earth’s Future, p.e2020EF001874.

Koch, A., Brierley, C. and Lewis, S.L., 2021. Results of Earth system feedbacks on the potential mitigation of large-scale tropical forest restoration. Biogeosciences, 18(8), pp.2627-2647.

Saatchi, S., Longo, M., Xu, L., Yang, Y., Abe, H., André, M., Aukema, J.E., Carvalhais, N., Cadillo-Quiroz, H., Cerbu, G.A. and Chernela, J.M., 2021. Detecting vulnerability of humid tropical forests to a number of stressors. One Earth, 4(7), pp.988-1003.

Xu, L., Saatchi, S.S., Yang, Y., Yu, Y., Pongratz, J., Bloom, A.A., Bowman, Ok., Worden, J., Liu, J., Yin, Y. and Domke, G., 2021. Adjustments in international terrestrial dwell biomass over the twenty first century. Science Advances, 7(27), p.eabe9829.

[ad_2]