[ad_1]

On an expedition with the Schmidt Ocean Institute off the coast of San Diego in August 2021, MBARI despatched the pair of instruments—together with a specialised DNA sampling equipment—a whole bunch of meters deep to discover the midwaters. The researchers used the cameras to scan at the least two unnamed creatures, a brand new ctenophore and siphonophore.

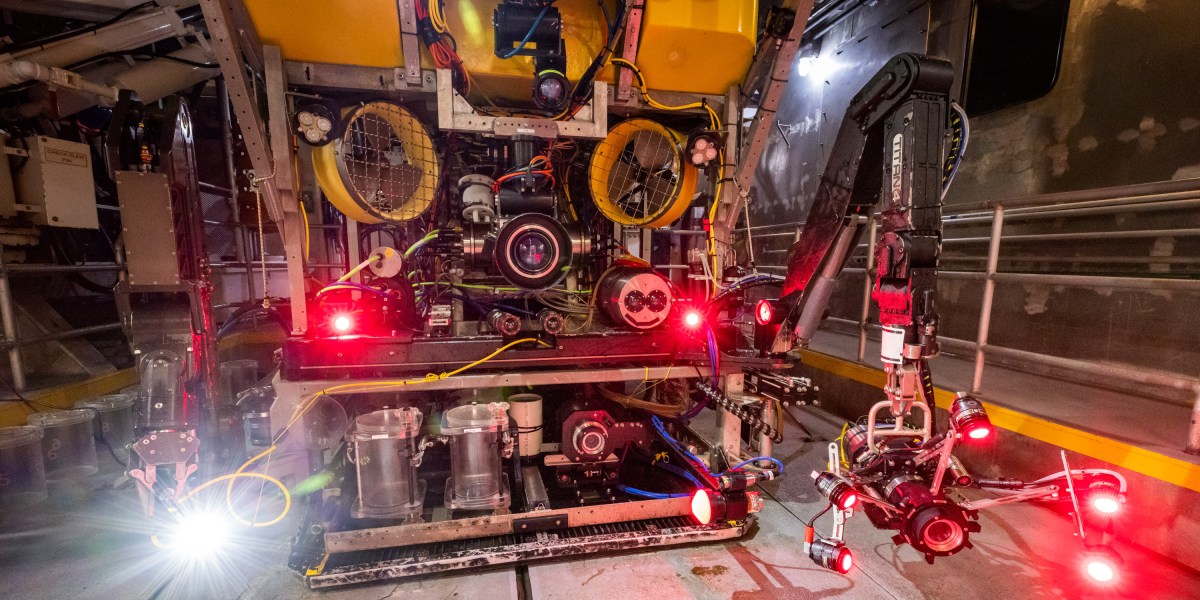

JOOST DANIELS © 2021 MBARI

The profitable scans strengthen the case for digital holotypes—digital, fairly than bodily, specimens that may function the idea for a species definition when assortment isn’t doable. Traditionally, a species’ holotype has been a bodily specimen meticulously captured, preserved, and catalogued—an anglerfish floating in a jar of formaldehyde, a fern pressed in a Victorian ebook, or a beetle pinned to the wall of a pure historical past museum. Future researchers can study from these and evaluate them with different specimens.

Proponents say digital holotypes like 3D fashions are our greatest likelihood at documenting the variety of marine life, a few of which is on the precipice of being misplaced perpetually. With out a species description, scientists can’t monitor populations, establish potential hazards, or push for conservation measures.

“The ocean is altering quickly: growing temperatures, lowering oxygen, acidification,” says Allen Collins, a jelly skilled with twin appointments on the Nationwide Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Smithsonian Nationwide Museum of Pure Historical past. “There are nonetheless a whole bunch of 1000’s, even perhaps thousands and thousands, of species to be named, and we will’t afford to attend.”

Jelly in 4 dimensions

Marine scientists who analysis gelatinous midwater creatures all have horror tales of watching probably new species disappear earlier than their eyes. Collins recollects attempting to {photograph} ctenophores within the moist lab of a NOAA analysis ship off the coast of Florida: “Inside a couple of minutes, due to both the temperature or the sunshine or the strain, they simply began falling aside,” he says. “Their bits simply began coming off. It was a horrible expertise.”

Kakani Katija, a bioengineer at MBARI and the driving drive behind DeepPIV and EyeRIS, didn’t got down to remedy the midwater collector’s headache. “DeepPIV was developed to take a look at fluid physics,” she explains. Within the early 2010s, Katija and her staff had been learning how sea sponges filter-feed and needed a technique to observe the motion of water by recording the three-dimensional positions of minute particles suspended in it.

They later realized the system may be used to noninvasively scan gelatinous animals. Utilizing a strong laser mounted on a remotely operated automobile, DeepPIV illuminates one cross-section of the creature’s physique at a time. “What we get is a video, and every video body finally ends up as one of many pictures of our stack,” says Joost Daniels, an engineer in Katija’s lab who’s working to refine DeepPIV. “And when you’ve acquired a stack of pictures, it’s not a lot totally different from how individuals would analyze CT or MRI scans.”

Finally, DeepPIV produces a nonetheless 3D mannequin—however marine biologists had been keen to look at midwater creatures in movement. So Katija, MBARI engineer Paul Roberts, and different members of the staff created a light-field digital camera system dubbed EyeRIS that detects not simply the depth but additionally the exact directionality of sunshine in a scene. A microlens array between the digital camera lens and picture sensor breaks the sphere down into a number of views, just like the multi-part imaginative and prescient of a housefly.

PAUL ROBERTS © 2021 MBARI

EyeRIS’s uncooked, unprocessed pictures appear like what occurs while you take your 3D glasses off throughout a film—a number of offset variations of the identical object. However as soon as sorted by depth, the footage resolves into delicately rendered three-dimensional movies, permitting researchers to look at behaviors and fine-scale locomotive actions (jellies are specialists at jet propulsion).

What’s an image price?

Over the many years, researchers have sometimes tried to explain new species with out a conventional holotype in hand—a South African bee fly utilizing solely high-definition photographs, a cryptic owl with photographs and name recordings. Doing so can incur the wrath of some scientists: in 2016, for instance, a whole bunch of researchers signed a letter defending the sanctity of the normal holotype.

However in 2017, the Worldwide Fee on Zoological Nomenclature—the governing physique that publishes the code dictating how species needs to be described—issued a clarification of its guidelines, stating that new species may be characterised with out a bodily holotype in instances the place assortment isn’t possible.

In 2020, a staff of scientists together with Collins described a brand new genus and species of comb jelly based mostly on high-definition video. (Duobrachium sparksae, because it was christened, appears to be like one thing like a translucent Thanksgiving turkey with streamers trailing from its drumsticks.) Notably, there was no grumbling from the taxonomist peanut gallery—a win for advocates of digital holotypes.

Collins says the MBARI staff’s visualization strategies solely strengthen the case for digital holotypes, as a result of they extra carefully approximate the detailed anatomical research scientists conduct on bodily specimens.

A parallel motion to digitize present bodily holotypes can also be gaining steam. Karen Osborn is a midwater invertebrate researcher and curator of annelids and peracarids—animals rather more substantial and simpler to gather than the midwater jellies—on the Smithsonian Nationwide Museum of Pure Historical past. Osborn says the pandemic has underlined the utility of high-fidelity digital holotypes. Numerous subject expeditions have been scuttled by journey restrictions, and annelid and peracarid researchers “haven’t been in a position to go in [to the lab] and have a look at any specimens,” she explains, to allow them to’t describe something from bodily sorts proper now. However examine is booming by way of the digital assortment.

Utilizing a micro-CT scanner, Smithsonian scientists have given researchers world wide entry to holotype specimens within the type of “3D reconstructions in minute element.” When she will get a specimen request—which usually includes mailing the priceless holotype, with a threat of harm or loss—Osborn says she first presents to ship a digital model. Though most researchers are initially skeptical, “with out fail, they all the time get again to us ‘Yeah, I don’t want the specimen. I’ve acquired all the knowledge I want.’”

“EyeRIS and DeepPIV give us a method of documenting issues in situ, which is even cooler,” Osborn provides. Throughout analysis expeditions, she’s seen the system in motion on big larvaceans, small invertebrates whose intricate “snot palaces” of secreted mucus scientists had by no means been in a position to examine utterly intact—till DeepPIV.

Katija says the MBARI staff is pondering methods to gamify species description alongside the traces of Foldit, a preferred citizen science undertaking through which “gamers” use a video-game-like platform to find out the construction of proteins.

In the identical spirit, citizen scientists may assist analyze the photographs and scans taken by ROVs. “Pokémon Go had individuals wandering their neighborhoods on the lookout for pretend issues,” Katija says. “Can we harness that vitality and have individuals on the lookout for issues that aren’t recognized to science?”

Elizabeth Anne Brown is a science journalist based mostly in Copenhagen, Denmark.

[ad_2]